Columbia Riverkeeper’s Q & A breaks down why environmentalists should stand in solidarity with tribal nations and oppose this so-called “green energy” project.

What’s proposed?

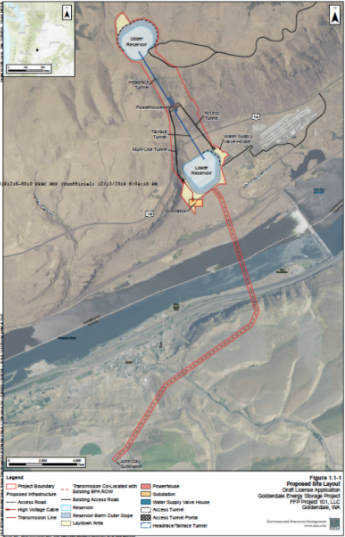

Rye Development wants to build a massive pumped storage hydroelectric project along the Columbia River’s banks in Klickitat County, Washington, near the John Day Dam. The Goldendale Energy Storage Hydroelectric Project would be the largest of its kind in the Northwest.[1]

Rye would excavate two reservoirs: the hilltop reservoir would span 60-acres and the lower reservoir would cover 63-acres (i.e., surface area). Pumped storage generates hydroelectricity for peak periods of demand. When electricity on the grid is abundant, Rye would pump water from the lower reservoir into the higher one. Then, when there’s demand for electricity, Rye would release water in the upper reservoir through turbines and back into the lower reservoir. The energy-generating capacity: 1200 megawatts.

Rye claims the $2 billion project would be complete by 2028.

Have impacted tribal nations weighed-in on Rye’s proposal?

Yes. The Confederated Tribes and Bands of Yakama Nation (Yakama Nation) has opposed this development from the start. The development would impact sacred cultural resources, “including archeological, ceremonial, burial petroglyph, monumental and ancestral use sites.”[2]

Here’s how a Yakama Nation representative explained the Tribe’s opposition at a Washington State Senate hearing in early 2020:

“As you’re aware, the Columbia River was dammed over the last century. In doing so, that impacted many of our rights, interests and resources. All of these things have been impacted: our fish sites, our villages, our burial sites up and down the river. This is another example of energy development, development in the West, that comes at a cost to the Yakama Nation.”

Rye’s development would directly interfere with at least nine culturally significant sites to the Yakama Nation and other cultural property. Cultural property is defined as “the tangible and intangible effects of an individual or group of people that define their existence, and place them temporally and geographically in relation to their belief systems and their familial and political groups, providing meaning to their lives.[3]

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) also weighed in during the initial licensing process. Due to the intensely sensitive nature of cultural resources, letters submitted by CTUIR may not be accessed by the public in order to safeguard any information about cultural resource locations and items that they may contain.

Does the development use a lot of water?

Yes. Initial fill for the reservoirs would use 2.93 million gallons of Columbia River water. Rye would also use roughly 1.2 million gallons of water per year from the Columbia for “periodic makeup” to offset losses from evaporation and leakage.

There is also the possibility of refill if the reservoirs need to be emptied for repair. Rye calls the project “closed-loop,” a misleading description when you consider the company’s plans to use Columbia River water to sustain the reservoirs.

Does the Pacific Northwest need this development to combat climate change?

No. According to a third-party economic analysis, the development cannot provide renewable energy integration and replacement capacity to support regional decarbonization goals affordably and reliably.[4] Why? A combination of rising construction costs and decreasing open-market energy prices.

How does the development impact wildlife?

The project will have serious impacts on wildlife in the area. The introduction of two large water surfaces will attract many birds to the area, which is located near a large wind energy project. Wildlife biologists have raised concerns that the reservoirs would attract more birds to the area and increase wind-turbine bird kills. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has repeatedly discussed the presence of bald and golden eagle and prairie falcon nests in the area. In describing the history of golden eagle deaths in the area, USFWS explained:

“This history of mortalities shows a landscape already compromised by wind power infrastructure. Currently golden eagles appear to have a difficult time navigating the wind currents affected by existing wind power infrastructure near the project area. The potential of the proposed Project to further alter the remaining laminar wind currents lends credence that resulting impacts to avian species would not be exclusive to wind power production in the area.”[5]

USFWS has also voiced concerns that the developer’s plans to mitigate habitat loss and manage wildlife appear to look more like minimizing impacts rather than mitigating impacts.[6]

Is the project financially viable?

Pumped storage requires significant upfront capital investment and lengthy permitting processes. Experts question the financial viability of the project. Rocky Mountain Econometrics (RME) developed a model of market forces and financial viability of the project, based on data provided by the developer. RME concluded:

“It is possible that the Goldendale Pump Storage Project is being proposed with full knowledge that it will fail. Further, bankruptcy may be an unstated but integral part of the Goldendale business plan as a means of shedding sufficient debt to survive in the current wholesale power market. These results, as detailed in the report’s Appendix Alternative Debt Structures, give us pause as to whether any adverse impacts to public values such as water quality, water quantity, flow regime, fish and wildlife, tribal and cultural resources, surrounding communities, and/or recreation are worth the risk and generated energy storage.”

Bottomline: the developers cause the loss of irreplaceable cultural resources and environmental destruction for speculative benefits.

Did the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) deny a pumped storage proposal at a similar location?

Yes. FERC denied a different developer a license in 2016. Developers want to build the lower reservoir at the site of a former aluminum smelter. The problem: toxic pollution in soil and groundwater. FERC concluded that developers should complete the cleanup before securing a license for new development.

What’s the regulatory process to build a development of this scale?

Rye needs a hydropower license from FERC and a Clean Water Act 401 water quality certification from the Wash. Dept. of Ecology. Rye already secured water rights for the project. The project will also undergo federal National Environmental Policy Act and Endangered Species Act reviews. Rye estimates FERC will release a draft Environmental Assessment or Environmental Impact Statement in summer 2021. After the FERC process, the developer will need to apply to the Bonneville Power Administration for transmission interconnect approval.

What can I do to stand in solidarity with tribal nations opposed to this energy development?

Sign our petition asking Gov. Inslee and Senators Murray and Cantwell to stand in solidarity with tribal nations who oppose this hydroelectric development.

Additional Resources:

- For more in depth analysis, read Riverkeeper and Friends of the White Salmon’s Comments on Rye Development’s Draft License Application

- Read more about the historical context surrounding the treatment of Indian remains and cultural resources in the United State: “Indian Remains, Human Rights: Reconsidering Entitlement Under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act” by Angela R. Riley.

- Rocky Mountain Econometrics Report

- Yakama Nation Comment on Rye Development’s Notification of Intent and Pre-Application Document.